In the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, few of us think about the dirt under our feet. Sure, we rightly pay attention to the usual lineup of offenders–power plants, congested roadways, and other major emissions sources. But rarely do we consider that one of our great potential allies in the fight against climate change is the soil that’s all around us. One unlikely, but major, way we get the land to work for us by trapping more carbon emissions? Software.

Green software?

Rather than a tool to reduce emissions, running software is generally thought of as a serious energy consumer, and therefore a carbon polluter. Experts estimate that Internet companies’ massive data centers emit as much carbon dioxide as the airline industry. Because of this, the biggest technology businesses have taken steps to run their facilities and supply chains sustainably and invest in climate solutions (see Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Apple). These solutions range from offsetting carbon emissions — essentially paying people who otherwise would have emitted carbon not to do so — to reducing overall emissions of all those servers by running them on green energy.

But software can be more than a source of lower carbon emissions, it can actively help agriculture, forestry, and other intensive land-use industries decrease their carbon footprint. And there’s significant room for improvement: After energy production, these sectors are the next largest emissions sources, outstripping even transportation in terms of greenhouse gasses released into the air.

There are many reasons why. Modern farming practices usually result in farmers releasing carbon from the soil. Deforestation, meanwhile, destroys valuable carbon sinks and releases soil carbon into the atmosphere. And methane from livestock makes up a massive portion of greenhouse gas emissions.

Software can help keep carbon in the ground and in biomass by helping food producers, conservation organizations, governments, and other actors prevent its release into the atmosphere.

Deforestation monitoring

One example of useful software on this front are deforestation monitoring and measurement tools. In addition to being vital ecosystems, forests are massive carbon repositories sequestering hundreds of millions of tons of the element every year. This is why we dedicate so much attention to our rapidly diminishing rainforests in the Amazon and other hotspots; as trees fall, so does our biosphere’s capacity to remove atmospheric carbon. Monitoring forest changes is the first step toward taking action to address it.

One method for monitoring deforestation is by providing users with low-cost access to recent satellite images. In the past five years, public satellite initiatives like the European Space Agency’s Sentinel Program and the private satellite company Planet have made high-resolution multi-spectral satellite imagery more available than ever. Academics and activists have harnessed these and other data sources to use this imagery to detect where deforestation is occurring. Global Forest Watch is one of the best known examples of a worldwide deforestation tracker that uses this imagery. Developed by the World Resources Institute, this tool not only gives viewers a global history of forest change, but it can also alert users where deforestation is occurring in near real time. Some conservation organizations have created their own solutions that work on the same principle at a local level — in Peru, for example, the government has partnered with GIS specialists to create the Geobosques platform to monitor changes in the Amazon rainforest.

Forest-monitoring software creators are now democratizing these advanced tools for anyone to use. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization has developed a free and open-source satellite imagery tool called Sepal, which lets users gather recent satellite imagery from Google Earth Engine and train a computer to measure a variety of changes in their own local landscape. In some cases, deforestation notifications from this service can come rapidly — within several weeks.

Land protectors can also deploy technology to monitor deforestation on the ground, even in places where Internet access is limited. In Peru, the Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka indigenous groups use the offline data-collection tool Mapeo to track and report illegal mining and logging activities in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. By designing software to fit a resident’s needs and constraints like connectivity, such tools can help users reduce deforestation and the harmful environmental effects that accompany it.

Build knowledge on the ground to keep carbon in the ground

In recent decades, the practice of tilling, spraying with herbicides, and dousing the soil with nitrogen has caused damage to soil health worldwide. Experts project that if nothing changes in our agricultural practices, we will deplete most of our topsoils within the next 60 years. In this way, the struggle to reduce carbon emissions is deeply tied to our struggle to sustainably feed ourselves, and solutions for both crises focus on producing healthy soil with carbon stored where it belongs in the ground.

Software can help people who generate food from the earth — farmers, ranchers, fishers, and others — apply new methods like cover cropping and agroforestry to grow and harvest food while restoring soil. Tools, like those produced by Precision Development, send farmers — many of whom lack smartphones — SMS messages with day-to-day customized guidance on how to implement these best practices.

Mobile storytelling tools, meanwhile, enable activists to share their elders’ stories about how agricultural practices have changed the landscape they remember, encouraging younger generations to prevent erosion and maintain healthy soils.

Some software combines various sources of data with agricultural research to provide recommendations at the planning stage of crop selection and planting. For example, two agroforestry tools, the Agroforestry Platform and Pretaterra, help farmers plan agroforestry systems by guiding them on tree selection, spacing, and varietal combinations, as well as helping them to project yields and carbon sequestration. Other tools teach farmers and ranchers about regenerative practices. Using these software tools for planning and learning, people who gather resources from the land emit fewer greenhouse gases.

Financial incentives for ecosystem services

Market forces play a large role incentivizing agricultural practices that degrade soil quality and release carbon into the atmosphere. As populations increase, so does the demand for large volumes of high-calorie foods. So-called “Green Revolution” practices of high tillage as well as heavy use of pesticides and fertilizers can result in farmers producing high yields, but at the cost of soil degradation. Regenerative practices can generate healthy food and soil (as well as greater profits), but transitioning to such approaches is a costly unknown for farmers working with narrow profit margins. Software can ease the transition by providing the infrastructure for farmers and other people who manage the land to be compensated for following practices that store carbon in plants and the soil.

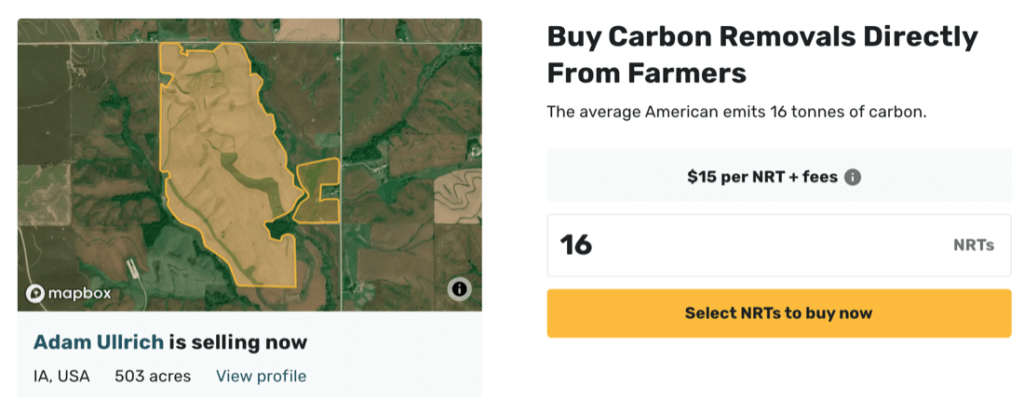

Software can also help in tracking and maintaining carbon-credit financial systems. Platforms like Regen Network and Nori allow third parties to purchase from producers a carbon sequestration behavior like cover cropping, or rotational grazing. Today on Nori, for example, I have the option to spend $276 to purchase 16 tonnes of carbon removal from a farmer in Iowa (the average American emits 16 tonnes of carbon a year). Tools like these deliver money producers that can keep carbon in the soil, where it benefits everyone.

Another critical approach is the process of certification. Certification means a third party reviews how farmers grow crops and issues a seal of approval which increases their value. Certification programs such as those developed by the Rainforest Alliance promote sustainable agriculture by encouraging farmers to preserve forests and adopt sustainable practices. Software can aid in this process by allowing farmers to keep accurate records of their practices, inputs, and outputs — all the necessary information for a certifier to deliver the seal of approval.

Software is a piece of the puzzle

As a part of the 1000 Landscapes for One Billion People initiative, Tech Matters plays the main technology solutions role. We’re building the Terraso software platform to meet the needs of local leaders around the world to help them have the information, tools and funding to build the regenerative local economies of the future. Equally important to creating our software is to identify and celebrate the work being done by other great groups such as those we’ve highlighted above. By interconnecting others’ software tools and sharing best practices we can help local leaders plan, fund, and execute projects that benefit both their local and the broader global community.

Healthy soils and atmospheric carbon reduction requires the efficient transfer of information between actors. Verifiable data is a critical component of land management — allowing all stakeholders to know with confidence what is happening and how the land is changing so they can convince others of the need to act. To the extent that software can record data, provide it to the people who need it and help people organize and communicate effectively, it is a critical component of helping people deliver ecosystem services like keeping carbon in the ground.

Systemic problems like climate change can only be addressed with systemic solutions, with myriad actors pursuing change in their own locale and context (and the World Economic Forum recently published our article on this topic). Green software may not garner the headline attention of the latest electric car, but it is necessary to sustainably manage our lands, restore degraded ecosystems and help communities around the globe address a changing climate.

Thanks for highlighting how software can play a role in solving environmental and food security challenges. It’s hard to believe that Internet companies’ massive data centers emit as much carbon dioxide as the airline industry (I certainly hope not!) but easy to believe that software, TechMatters and 1000 Landscapes can help strengthen the good work and deliver the good ideas that will help local actors make progress on the path to more regenerative practices….!