As 2024 begins, we reflect on the steps we’ve made towards our ambitious goal of empowering one thousand landscapes with critical software tools.

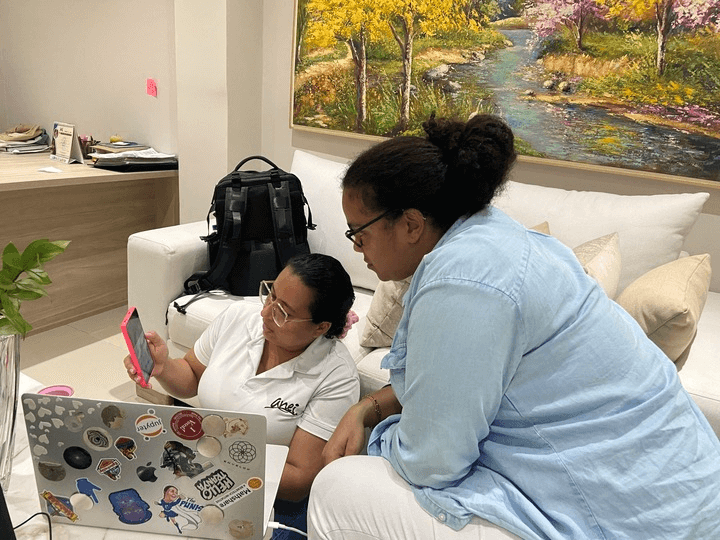

2023 marked a significant milestone for Terraso, culminating in the launch of our product in Kenya, before a crowd of landscape practitioners. This launch wasn’t just about unveiling a tool we meticulously developed; it was an opportunity to share the result of a years-long collaboration with design partners. Engaging closely with communities, we gained invaluable insights into their requirements, insights that have been instrumental in shaping our product. As the new year begins, we think back on the guidance we received that day, as well as the feedback we received from co-design partners in South America throughout 2023. It has guided our journey up until now and remains a driving force to ensure that we Terraso keeps evolving to meet the needs of the landscapes we serve.

Building Upon Foundations in User Research

Terraso’s launch in May was the result of more than two years of concerted effort. We engaged with numerous landscape leaders, dedicating over 200 hours to conversations with co-design partners. We learned that landscape managers are confronted with a variety of technological challenges that impede their ability to achieve their goals. Many of the people we spoke to:

- lacked access to tools for effective data gathering and meaningful monitoring and evaluation;

- confronted silos within their landscapes which restricted sharing information among stakeholders, impeding collaboration and decision-making;

- were challenged in deciphering complex data;

- needed better maps to aid communication and understanding. Whether drawn in a workshop or generated from satellite imagery, maps help to explain the status of the land and people’s vision for the future.

An early conversation with Percy Summers (Conservation International, Peru) left a lasting impression on understanding the importance of maps. Aerial footage and maps transformed the dynamics of a gathering of indigenous actors. A map broke through the morass of a workshop. It quickly generated a shared understanding and consensus among participants:

“One of my first lessons: I went to this indigenous community where we were trying to get buy-in to work with them. We were talking for an hour about all the threats and issues that the community had. It was a one-hour conversation that was going nowhere. And then I finally pulled out the map, which I had printed out in a big format.

In five minutes. I mean, in five minutes, they saw the deforestation around the community, they saw it and could visualize how forest loss was much more evident through that map. We were totally engaged and they gave us their total attention. So, from then on, I use maps a lot. Just to start conversations: scenarios for coffee like when you want to start talking about what’s going to happen 10 years, 20 years, 30 years from now. You do the projections of deforestation and take those maps to the workshop, and you start with that.”

For Percy, then and throughout his career, maps are a critical communication tool. In a conversation with Eddy Mendoza (another CI specialist), we learned just how hard it was to create maps. His community lacks GIS experts, not due to a lack of inherent abilities among the people in the community, but because the tools were always designed for different audiences—, English-speaking and trained in advanced technologies.

“It is necessary to create mapping tools [that are] very, very simple. Friendly. In Spanish, too. That’s important. Because when you create some tools, and when you’re training the technical person in their regions or regional government, for example. The majority don’t speak English. I recommend, when you create Terraso, you do it in Spanish, too.”

The conversations and hundreds of early Terraso interviews convinced us that to succeed, landscape members needed easy access to data and mapping tools. These tools need to be easy-to-use and available in each user’s language.

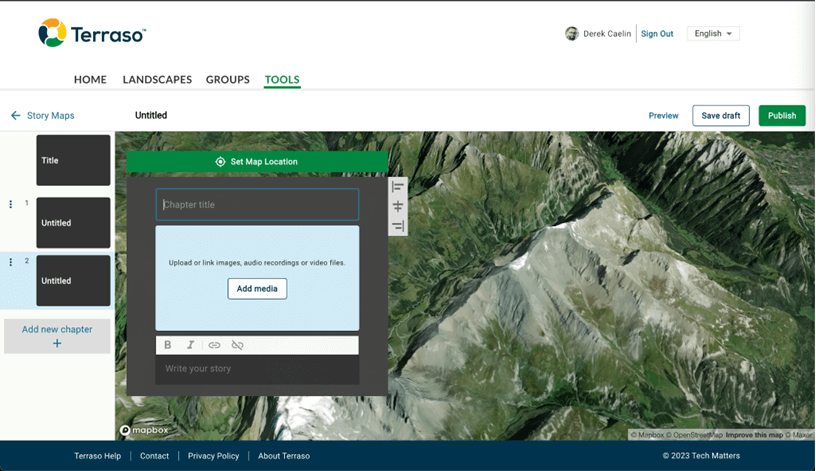

The Journey to Story Maps

With this feedback as guidance, we incorporated maps into Terraso in several ways. We trained partners in the use of KoboToolbox, a data collection tool which enables the capture of geospatial data. We allowed users to quickly build maps from a CSV or Excel file. However, our biggest success came when we discovered our community’s interest in story maps.

From time to time, we encountered story maps in our research of relevant tech in the environmental space, many of which were powered by Esri products. The owners of these story maps were proud of their creations, but troubled. They told us they often needed to hire a GIS consultant to spend several months putting these stories together. From our co-design partners, we knew that map-based narratives were in high demand, so we decided to build value by breaking down barriers to story mapping and providing a free and easy-to-use alternative. We started to research open source options. We found promising examples in Knight Lab’s StoryMapJS and a project to use Leaflet to build story maps with Google Sheets. When we discovered Digital Democracy’s project portfolio, we realized they had tapped into another powerful tool created by Mapbox. While the tool didn’t provide a friendly user interface for creating story maps, it presented text and media alongside smooth transitions across a map of a landscape. We had discovered a powerful storytelling tool. Now we had to confirm that it could meet the needs of our co-design partners.

Building Through Collaboration

To validate our hypothesis, we began by prototyping and testing with our partners before we jumped into development. We reached out to Conservation International (CI) in Guyana and the ALDEA Foundation in Ecuador hoping they would be interested in building a story map with us. Both used maps frequently in their work and had talented storytellers on their teams. We presented the tool and proposed a collaboration. We would help these groups build a story map. In turn, they would provide us with feedback on what they needed the tool to do and how they needed it to behave. Two brilliant story maps emerged through this collaboration, each offering lessons learned.

The Mud that Makes Us, by Damian Fernandes of Conservation International, Guyana

Damian Fernades is a senior advisor to CI in Guyana. CI has been advocating for sustainability solutions throughout his country. When we first spoke, Damian was particularly interested in raising awareness of the dangers on the coastline. He wanted to highlight how the status quo building strategy was untenable. Flooding was destroying livelihoods along the Guyanese coast. It was also costing the local government millions of dollars in continual repair work. Damian wanted to use maps to convey how a more sustainable solution was possible. He combined different engineering approaches to produce a living, mangrove-protected coastline. In building this story map, Damian stretched our understanding of what the story needed to convey. The map zoomed out to see the entire country, and it refocused on minute details of the coast. Damian wanted to display images on the surface of the map. He also wanted to share pictures and videos from the landscape, from the verdancy of mangroves to the force of the waves battering the concrete coastline. We learned that our tool needed to do all this. It also needed to allow the user to seek out specific points of interest on the land and to allow the user to collaborate with others.

Damian had some wonderful things to say about the experience of using Terraso:

“Personally, I think Terraso’s story map tool is a turning point in how we tell stories. Through its accessibility, it offers something deeply transformational for countries like mine, where many forgotten human stories have played out on our shared landscapes. Uncomfortable by true stories of colonization, enslavement and indentureship; stories of how our ancestors shaped and reshaped this land, leaving marks that can be seen from space. Marks that seem to speak from our past, saying ‘we were here’.

Terraso provides a platform to hold these different stories, in all their complexities and contradictions, and show us the true meaning of our shared Guyanese identity. This tool has already helped us to tell the story of the natural “earth engine” that pulled Guyana’s fertile coast out of the Atlantic. A hidden phenomenon that was interrupted centuries ago, but that can now be restarted to save our increasingly vulnerable coast. I think this story map, and the countless others still to be shaped, will allow us as Guyanese to dream new dreams for the future of our landscapes and our people; dreams I like to think our ancestors would be proud of.”

Damian uses The Mud that Makes Us to advocate for a “Green-Grey” coastline that combines legacy concrete infrastructure with mangroves to capture soil and protect the coastline. Today, we are exploring a partnership with CI-Guyana. We aim to strengthen a community of indigenous Guyanese people’s capacity to use storytelling technologies.

Tierras En Conflicto, by the ALDEA Foundation

The ALDEA Foundation represented an ideal organization for us to work with. They already used open source tools to gather data and stories about people within a landscape. They were looking for ways to improve the accessibility of the data. ALDEA’s story focused on the tragic externalities of global climate finance. They interviewed hundreds of people who struggled with a company which was claiming ownership of their land to steal their forest protection incentives. ALDEA had already published their data in an open source map but wanted to make the story accessible to a wider audience.

We learned from Tierras En Conflicto the importance of showcasing geospatial data. This data often comes in multiple layers and formats. ALDEA wanted to show how a company’s fraudulent land ownership claims impacted communities who had been denied access to conservation benefits.

Based on these collaborations, we knew that it would be worthwhile to dedicate design and engineering resources to enhancing the Mapbox story map offering. We designed an experience for users to create story maps without writing any code. Because of our previous interviews, we knew we had to make this experience as simple as possible. Since we knew most of our users were familiar with slide decks like PowerPoint and Google Slides, we felt confident that we could pull from those tools to guide our own user experience.

We want to highlight these two story maps and the things we learned while co-creating them, but we’d be remiss if we didn’t thank all the partners who participated in usability testing for the products. Thank you to Luami Zondagh near the Gouritz Biosphere reserve in South Africa, the ANEI cooperative in Colombia, members of KenLAP in Kenya, and forest entrepreneurs in Mexico City for using Terraso and providing feedback.

Their feedback has been critical to helping us to prioritize the enhancements we plan for Terraso. After the 2023 launch, these updates included allowing embedding story maps in websites and blogs to provide greater flexibility. Users can now reorder chapters and upload small videos. They can also collaborate with others by inviting users to become editors.

LandPKS for Land Stewards

While part of our team worked on story maps, another part was hard at work on a new tool in Terraso’s toolbox: LandPKS. For more than a decade, LandPKS has helped land stewards like ranchers and farmers to identify their soils and make decisions about how to sustainably manage the land.

Tech Matters is partnering with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and scientists from universities in New Mexico and Colorado to redesign the LandPKS app, making it easier to use. We’ll be launching LandPKS this year—stay tuned for a longer update about the project.

2023 was the year that we (finally!) were able to bring our hard work on landscape technology to the public. Our launch was the culmination of years of speaking with and learning from landscape leaders, and we have not stopped learning. Our efforts in 2024 will continue to meet their needs through a process of collaboration, feature improvements, and of course new releases. Happy 2024 to everyone and we hope you are as excited as we are for what this year has in store for Terraso!